-

|

-

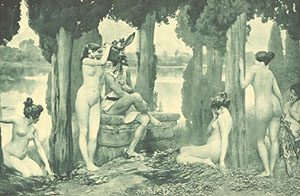

MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM

-

An original painting by P. Gervais

|

|

| A Midsummer Night's Dream and The Tempest may be so far compared that in both the influence of a wonderful world of spirits is interwoven with the farcical adventures of folly. A Midsummer Night's Dream is certainly an early production; but The Tempest, according to all appearance, was written in Shakespeare's later days. Hence, most critics, on the supposition that the poet must have continued to improve with increasing maturity of mind, have honored the later piece with a marked preference. |

|

The internal merit of the two works are, however, about evenly balanced, and a predilection for the one or the other is a matter of personal taste. In profound and original characterization the superiority of The Tempest is obvious: as a whole we must always admire the masterly skill which he has here displayed in the economy of his means, and the dexterity with which he has disguised his preparations--the scaffoldings for the wonderful aerial structure.

In A Midsummer Night's Dream, on the other hand, there flows a luxuriant vein of the noblest and most fantastical invention; the most extraordinary combination of very dissimilar ingredients seems to have brought about without effort by some ingenious and lucky accident, and the colors are of such clear transparency that we think the whole of the variegated fabric may be blown away with a breath. The fairy world here described resembles those elegant pieces of arabesque, where little genii with butterfly wings rise, half embodied, above the flower-cups. Twilight, moonshine, dew and spring perfumes are the element of these tender spirits; they assist nature in embroidering her carpet with green leaves, many-colored flowers and glittering insects; in the human world they do but make sport childishly and waywardly with their beneficent or noxious influences. Their most violent rage dissolves in good-natured raillery; their passions, stripped of all earthly matter, are merely an ideal dream. To correspond with this, the love of mortals is painted as a poetical enchantment which, by a contrary enchantment, may be immediately suspended and then renewed again. The different parts of the plot; the wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta, Oberon and Titania's quarrel, the flight of the two pair of lovers, and the theatrical manœuvres of the mechanics, are so lightly and happily interwoven that they seem necessary to each other for the formation of the whole.

Oberon is desirous of relieving the lovers from their perplexities, but greatly adds to them through the mistake of his minister, till he at last comes really to the aid of their fruitless amorous pain, their inconstancy and jealousy, and restores fidelity to its old rights. The extremes of fanciful and vulgar are united when the enchanted Titania awakes and falls in love with a coarse mechanic with an ass's head, who represents, or rather disfigures, the part of a tragical lover. The droll wonder of Bottom's transformation is merely the translation of a metaphor in its literal sense; but in his behavior during the tender homage of the Fairy Queen we have an amusing proof how much the consciousness of such a head-dress heightens the effect of his usual folly. Theseus and Hippolyta are, as it were, a splendid frame for the picture; they take no part in the action, but surround it with a stately pomp. The discourse of the hero and his Amazon, as they course through the forest with their noisy hunting-train, works upon the imagination like the fresh breath of morning, before which the shapes of night disappear. Pyramus and Thisbe is not unmeaningly chosen as the grotesque play within the play; it is exactly like the pathetic part of the piece, a secret meeting of two lovers in the forest, and their separation by an unfortunate accident, and closes the whole with the most amusing parody.

"I am convinced," says Coleridge, "that Shakespeare availed himself of the title of this play in his own mind, and worked upon it as a dream throughout." The poet, in fact, says so in express words:

- If we shadows have offended,

- Think but this (and all is mended),

- That you have but slumber'd here,

- While these visions did appear.

- And this weak and idle theme,

- No more yielding but a dream,

- Gentles, do not reprehend.

But to understand this dream--to have all its gay and soft and harmonious colors impressed upon the vision, to hear all the golden cadences of its poesy, to feel the perfect congruity of all its parts, and thus to receive it as a truth, we must not suppose that it will enter the mind amidst the lethargic slumbers of the imagination. We must receive it

- As youthful poets dream

- On summer eves by haunted stream.

No one need expect that the beautiful influences of this drama can be truly felt when he is under the subjection of literal and prosaic parts of our nature; or, if he habitually refuses to believe that there are higher and purer regions of thought than are supplied by the physical realities of the world. If so, he will have a false standard by which to judge of this, and of all other high poetry--such a standard as that of the acute and learned critic, Dr. Johnson, who lived in a prosaic age, and fostered in this particular the ignorance by which he was surrounded. He cannot himself appreciate the merits of A Midsummer Night's Dream: "Wild and fantastical as this play is, all the parts in their various modes are well written, and give the kind of pleasure which the author designed. Fairies, in his time, were much in fashion; common tradition made them familiar, and Spenser's poem had made them great." And thus old Pepys, with his honest hatred of poetry: "To the King's theatre, where we saw A Midsummer Night's Dream, which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid, ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life."

Hallam accounts A Midsummer Night's Dream poetical more than dramatic; "yet rather so, because the indescribable profusion of imaginative poetry in this play overpowers our senses, till we can hardly observe anything else, than from any deficiency of dramatic excellence. For, in reality, the structure of the fable, consisting as it does of three, if not four, actions, very distinct in their subjects and personages, yet wrought into each other without effort or confusion, displays the skill, or rather instinctive felicity, of Shakespeare, as much as in any play he has written."